Wednesday, August 29, 2007

Honey, I'm home!

If at least one of my fellow passengers is a woman sporting a dubi-dubi, I know I'm probably headed to PR.

If on my way to baggage claim at the Luis Muñoz Marín airport I see more people holding signs bearing the logo of a resort than actual passengers, I know I'm in PR.

If I exit the terminal and walk right into humidity so thick that it bounces me back a couple of feet, I know I'm in PR.

If I get in my mom's car and head straight into a traffic jam, I know I'm in PR.

If during the drive away from the airport I let out a sigh of contented relief, I know I'm in PR.

If I immediately develop a craving for fried fish and arepas from Los Pescadores, I know I'm in PR.

If I find myself actually craving Medalla Light, I know I'm in PR.

If I'm stepping into a panadería and find myself buying a dozen quesitos and a cuban sandwich the size of my head, and seriously consider eating them all myself, I know I'm in PR.

If it's 90 degrees and I'm having café con leche, and thinking about asopao for dinner, I know I'm in PR.

If during the ride to the airport I have to hold my breath so I won't cry, I know I'm leaving PR.

How do you know if you're in PR? Or, how do you know you are back home, wherever you're from?

Monday, August 27, 2007

Saturday, August 25, 2007

Timbers and Islanders

Puerto Rico's soccer team, the Islanders, are in the same league as the Timbers, so they play against each other twice during the regular season. One game is in Portland, the other in Bayamón. The Islanders first played during the 2004 season and I attended the game that was played in Portland. There were a few Puerto Ricans in attendance, judging by the random t-shirts featuring the PR flag that I saw on various fans. I decided not to sit with the Timbers Army, leaving Dave to join his friends in chanting against the Islanders. I just didn't have the heart to cheer against them even if I am a Timbers fan -- not to mention that I also root for the Islanders to win and succeed. In 2005 we missed the Timbers vs Islanders games because we were in Florida, but in 2006 we were back in Portland and were able to attend. This time I sat with the Army, although with the same misgivings that kept me away in 2004.

By halftime, I was feeling like a complete traitor. Clearly people were going to root against the Islanders, but sitting in such a vocal section made me feel like I was no longer straddling the line between my two homes. I was making a choice that I did not feel comfortable making. Dave tried to talk me into staying, because he enjoys it when I come to games with him, but he understood that I was feeling out of place. The last straw came when someone, out of a sense of extreme exuberance just as much as ignorance, yelled out something about "go back to your shacks".

I turned to Dave and said, "I'm leaving." At the same time, Dave was turning around to face the guy, who seemed to be all of 19 years old. Dave is 6'5" and when he wants to, he can look just as warm and inviting as a Mack truck barreling towards you. That look, as well as a "hey, man, knock that off", was enough to get the kid to apologize profusely. He in no way represented the Timbers Army as a whole, but I decided it was time to go sit elsewhere anyway for the rest of the game.

By the end of the match I had met a couple of Puerto Ricans and did manage to make plans to get together with them a few weeks later, which was a nice way to end the night. But later on, when Dave mentioned to another Timbers fan that I had decided to sit elsewhere for Timbers-Islanders games because of my divided loyalties, the person said "Well, you live in Portland now". In other words, I'm supposed to root for the local team and forget about any others. My immediate reaction was to say "If you moved to another city, would you forget about the Timbers?" That this had not occured to this person really surprised me. I assumed that even if they had never lived anywhere except their hometown, people would understand that living away from where one grew up means that sometimes you are torn in different ways between your old home and your new one. I suppose making that mental leap is not that easy. Maybe seeing someone with loyalties that lie in other places makes some people feel like their own home is not being afforded the respect they think it deserves. Regardless, it made the phrase "You're in America now" a lot more personal than I ever thought it would be.

Monday, August 20, 2007

The old and the new

Left: Rafael Tufiño, Cortador de caña, 1951

Right: Amolando, undated

Left: Rafael Tufiño, Goyita, 1953

Right: Woman with hoe, 1944-1947

Left: Rafael Tufiño, Vita cola, 1961

Right: Girl in pink dress in front of house, 1950's

The images in the paintings may seem somewhat nostalgic to a boricua, because the evoke another time and another way of life - one that our grandparents may still tell stories about. But a closer look reveals a kinship with reality which may be a bit softened by memory and aesthetics, but still bears resemblance to what life really looked like. The man in Amolando could be the same man as in Cortador de caña; not only is the job the same, but so are the surroundings, the attire, and the sense in both images of back-breaking work. Goyita (who is actually Tufiño's mother) shares the same skin color and look of determination as the Woman in Woman with hoe. Skin color in PR is varied, and the issues faced by those with dark skin were not only very close to Tufiño's experience, they were ones he chose to explore in his works. The girls standing in front of wooden houses in the last images share a similar sense of shyness mixed with curiosity as well as a similar background.

All three paintings above were done by Rafael Tufiño. I didn't concentrate on his works solely because they're good, but because his seemed to be the most available. It was disappointingly difficult to find a good number of images of Puerto Rican art on the internet, especially by those who worked in the earlier part of the 20th century. Many artists are referenced, as are their works, but not many images are available. Even images of works by Francisco Oller, PR's pre-eminent artist and close friend of the likes of Camille Pissarro and Paul Cezanne, are in short supply. Oller is a painter who should be more recognized internationally, but if we don't work harder to make sure our talent shines, he will remain a footnote in the biographies of his friends.

Just as our coastline is not all lost to the Marriots and the Hiltons, our countryside and its dwellings are not all lost to new cookie-cutter developments sprawling into once-green and lush landscape. We're more packed in, even out in the countryside, but we can still enjoy views that were also enjoyed by abuelo and abuela. Although the power cables are indeed not part of the bucolic landcascape of yore!

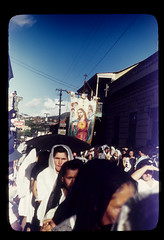

PR in the 1940's and 1950's

http://www.flickr.com/photos/tlehman

Thursday, August 9, 2007

Say what?

While there are many idioms of varying degrees of obscurity in the English language (ie, "between a rock and a hard place", "burn the midnight oil", "shoot the breeze"), I believe Spanish idioms - or as they are called in Spanish, dichos - may have an more colorful edge. Some examples of Puerto Rican dichos:

Más jala'o que un timbre de guagua

Literal translation: More pulled than a bus's bell

Sample sentence: I am so hungry that I am más jala'o que un timbre de guagua

This is a complicated one if you don't know the meaning of the term jala'o. First of all, it refers to the word halado, which, if you know a bit of Spanish, does not have an aspirated "j" sound (how the "h" sounds in English) because the letter H is silent. That's a somewhat common mispronounciation in PR, I find: to aspirate the "h" at the beginning of some words. We also tend to drop the -ado suffix and pronounce it "a'o", which sounds something like "a-u". People know it's wrong, but I suppose it's part of our accent. In any case, to feel jala'o is to feel so hungry that you feel the pit of your stomach start to sink, and is usually the precursor to hunger-induced nausea. So if you feel "pulled" then you can see where the dicho originated -- probably some poor soul who was starving while riding the bus, and in a particularly poetic moment was able to identify with the slacked and often-yanked cable of a bus bell. Also note that there is even a proper pronounciation for this entire idiom: you would never hear someone say "más halado que un timbre de guagua", rather, the words run together ("má' jala'o queun timbre'e guagua"). To say it properly would sound downright prissy. A proper Puerto Rican has nothing but disdain for the letters S and D.

Por un tubo y siete llaves

Literal translation: through a tube and seven faucets

Sample sentence: Lindsay Lohan has DUI's por un tubo y siete llaves

This idiom seeks to convey the image of something happening copiously. Again, with this one, once you know the meaning, you can understand the imagery. but unlike the previous dicho, I'm having a hard time imagining the moment the phrase was born. How many times do you find yourself in a situation where you are faced with seven faucets? And why seven, in particular? I suppose a young man could have been showering after gym class (or maybe he was in prison -- we need to keep our minds open here), marvelled at how one tube could feed so many faucets, and his inner philosopher emerged. In any case, this one makes me laugh because it reminds me of a day in my 5th grade English class where the teacher was asking us to come up with idioms, and my classmate Rafael spat out "by a tube and seven keys!" He said keys because the word llave means both faucet and key, and I'm guessing he had not yet deciphered what the phrase alluded to. Okay, maybe you had to be there.

Poner un huevo

Literal translation: Lay an egg

Sample sentence: This document cannot have any mistakes, so you can't poner un huevo.

How did "lay an egg" become synonymous with making a mistake? Laying eggs is natural, it's what chickens are supposed to do. A related dicho is meter la pata, which means to put in a leg. What? I don't get it; I can't even start to imagine how these were coined. Perhaps I don't want to let my mind go there, even if it could.

No se pierde un bautizo de muñecas

Literal meaning: He/she doesn't even miss a doll's baptism

Sample sentence: I was reading a copy of The Wall Street Journal, and I saw a picture of Paris Hilton hobnobbing with Alan Greenspan -- she'll go to any event, she won't even miss un bautizo de muñecas.

So what is a doll's baptism, you ask? I'll tell you. Just like little girls in the US, for example, will set up a tea party with their dolls, in PR girls used to baptize them. We're not just talking about sprinkling some water on their heads and calling it a day. They'd round them up, perhaps dress them up in white dresses, invite friends and family, and pretend to have a baptism. Someone would play the role of the priest, and I'm pretty sure the only "parent" present with the doll was the little girl herself. Single moms, perhaps? Scandalous. My neighbor Jenny did one, and in typical Jenny fashion the event was a blowout. Lots of neigbors came, the dolls were impeccable, and her brother Chago approximated a priest's garb and baptized the dolls. Other neighborhood girls brought their dolls too, to share in the beautiful moment, but Jenny's dolls were the stars of the show. In fact, her mother organized a doll beauty pageant and I actually had a role in this: I was to present the winner with her prize, which was a bottle of roll-on Avon perfume. The winner was - you guessed it! - Jenny's doll. Punch and cookies were served afterwards, and everyone agreed it was a beautiful ceremony.

Mas pela'o que el culo de un mono

Literal translation: More skinned than a monkey's ass

Sample sentence: Until payday, I am más pela'o que el culo de un mono.

The sample sentence should have shed some light onto the meaning of this saying: it means to be broke. Pela'o (pelado) technically means "skinned" and in our vernacular it means to not have any money. As far as pela'o goes, I can see the origin of the term (even more than I can understand how "broke" became English vernacular for the same thing). But the brilliance of this idiom is the introduction of a monkey's ass. If we follow the same technique of unlocking the origin of a saying by imagining what the person must have been doing in order to reach such an epiphany, then much fun can be had with this saying. And even if you don't care to think about monkey's asses, comparing anything to monkey's asses is just funny. Admit it.

Let's hear some other strange dichos, either in Spanish or in any other language!